CULTIVATING GROWTH AND SOLIDARITY

An Anti-Racism Zine for Asian Youth (and Adults too!)

August 2020

LAND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

With humility and gratitude, our team acknowledges that this project was co-created on the Homelands of the Lək̓ ʷəŋən, W̱SÁNEĆ, Sḵwx̱wú7mesh, Stó:lō, Səl̓ílwətaʔ, xʷməθkʷəy̓əm, K’ómoks, Snuneymuxw, and Quw’utsun’ Nations, colonial y known as Victoria, Vancouver, Hornby Island, and Galiano Island, BC. We recognize our place as Asians within the settler colonial project and continual y work to disrupt and dismantle oppressive systems we live within, which goes far beyond a land acknowledgement. As settlers and occupiers, we give ful -heart thanks to and uphold the sovereignty of these nations as peoples and caretakers of the land since time immemorial.

For more about land acknowledgements, please watch the short video, ‘Acknowledging Our Shared Territory,’ at https://vimeo.com/275778636.

Whose lands are you on?

We invite you to reflect on whose lands you currently and formerly reside upon, and what your relationship is to the land and the local Nation(s). You can use resources on the internet like https://native-land.ca/ or the website of local First Nations to help. As people who are far away from our ancestral homelands, we must be aware of whose lands we cal our (permanent or temporary) home, especial y because this land was not ceded or surrendered to the Canadian nation-state. So, whose lands are you on?

Use this space to write, draw, and reflect 🙂 With respect, we ask you to hold this information in your minds and hearts as you work through this zine and throughout your day to day lives.

THE HOW AND THE WHY

How to use this zine

Hi. 🙂 This zine is for you. That means you are encouraged to write, doodle, highlight, or mark it up in whatever way suits you best. You are also invited to work through it however you please, whether it is forward, backward, circling back, within a day, or over the course of a month. Al we can ask is for you to remain open to the process and engage with this zine in sincere and meaningful ways.

If something in this zine sparks your interest, we hope you follow that intrigue to learn more. Social media, blogs, youtube, and our website (www.growthandsolidarity.ca) are great resources, and we will include some links throughout these pages.

Thank you for being here and being a part of our community.

Why create this zine?

We wanted to create this zine because of the particular time and place we are in now with the COVID-19 pandemic, as wel as related anti-Asian racism, Black Lives Matter uprisings, and Indigenous land and water defenders asserting their rights and sovereignty. The world is changing quickly, but the foundation is centuries deep and people have been dreaming of change for many years. We also want to reduce and mend some of the harm perpetuated towards and by Asian people.

This zine is a part of how we can cultivate our individual and collective healing and growth.

SELF-LOCATIONS

Who are we?

Hi friends! My name is Qwisun Yoon-Potkins (윤귀선). I am a mixed-race Korean/English settler living on the unceded lands of the xʷməθkʷəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and səl̓ílwətaʔɬ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations. I’m a straight, cis, able-bodied woman, and the daughter of a Korean immigrant (mother) and Canadian-born English settler (father).

Hi everyone. 🙂 I’m Macayla Yan, and I am a Cantonese settler residing on Lək̓ ʷəŋən (“le-kwung-en”) and W̱SÁNEĆ (“wh-say-nech”) Homelands, aka Victoria, BC. My family comes from the tropical 中⼭ (Lau/劉/maternal family), 台⼭ (Yan/甄/paternal family), 澳⾨ (Lee/李/paternal family), and ⾹港 (Pang/彭/maternal family). I’m a queer, nonbinary, and chronical y il textile artist and graduate student studying counselling.

We also want to acknowledge our youth advisory team:

-

-

- Jenalyn Ng

- Kate Sun

- Maya Mersereau-Liem

- Ra’el Clark

-

What we did over there is self-locate ourselves. To self-locate is to understand our points of view and perspectives of the world within social and cultural contexts, with specific consideration of our ancestry and relationship to the lands we live on.

In other words, self-locations are a way to share with others what our culture and connections are. They are also linked to land acknowledgements because they include recognition of the lands you are currently on.

Self-locations are also a way to reject efforts to lump al people of the same racial group together. Importantly, self-locations are significant introductory protocols for many Indigenous Nations as well.

Where are you from?

No, really.

Although this question has been used against people of Asian descent, there is also power in knowing and being proud of where we are from.

With full recognition that people and society label us in ways that don’t always reflect who we actual y are, we provide this space for exploration of your personal self-location.

Some reflection questions: What is your family’s migration story? Where were your parents or grandparents born? What is your family’s cultural heritage? Where can you locate your family roots? If you are of multiple ethnic/racial backgrounds, what does being of mixed heritage mean to you? What are the limits of only identifying as Canadian? What is gained by identifying with your cultural heritage(s)? How has your family been affected by racism across generations? How has your family resisted racism across generations? What teachings has your family given you?

So, where are you really from?

DIASPORA

Let’s talk about diaspora.

Diaspora refers to a group or community of people who, despite not living on their ancestral homelands, maintain ties to their histories and heritage. Each diasporic community has a unique history. We invite you to explore yours, including experiences in ancestral homelands, while migrating, and in Canada. You can learn more by using the internet or even asking family members. These cultural ties significantly and uniquely impact a person’s identity and experiences over the life course.

The way in which cultural heritage is maintained may look different from person to person, and often varies even within families (see “intergenerational influences” on page 16). It is important to recognize the unique histories of the multitude of Asian cultures and ancestries that exist. We are not all the same!

INTERSECTIONALITY & POSITIONALITY

Intersectionality allows for a more nuanced examination of identity, which takes into account interconnected systems of oppression and marginalization. With intersectionality, we cannot only focus on one aspect of our identity.

Intersectionality includes considerations of …

-

-

- class…

- ability…

- sex/gender…

- age…

- colour…

- citizenship…

- race…

- sexual/romantic orientation…

- and much, much more!

-

Intersectionality is not a science or math. That means you cannot add East Asian + trans + girl to understand someone, but rather being an East Asian trans girl is a unique experience all together, greater than the sum of each part.

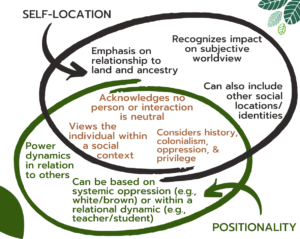

Positionality is similar to self-location, but different.

Because our self-locations and positionalities are intersectional, we can’t separate our Asian heritage from other parts of our identities.

Owning your positionality is an act of autonomy and integrity. Considering the concept of intersectionality (discussed on the previous page), write about your own understanding of your identity:

Image description: Venn diagram with one circle representing self-location and the other circle representing positionality. The self-location circle includes: 1) Emphasis on relationship to land and ancestry; 2) Recognizes impact on subjective worldview; and 3) Can also include other social locations/identities. The positionality circle includes: 1) Power dynamics in relation to others; and 2) Can be based on systemic oppression (e.g., white/brown) or within a relational dynamic (e.g., teacher/student). The overlap which encompasses both self-location and positionality includes: 1) Acknowledges no person or interaction is neutral; 2) Views the individual within a social context; and 3) Considers history, colonialism, oppression, & privilege.

CYCLE OF INTERNALIZATION

This is in the context of settler colonialism, which is a type of colonialism where colonizers settle on the land to replace the Indigenous population. Anyone who is not Indigenous is a settler. To learn more about this, check out the Settler Colonialism Primer at https://unsettlingamerica.wordpress.com/2014/1206/06/settler-colonialism-primer/

Start here:

-

- Born/enter into a society with an established culture, including beliefs, practices, and ideas (our inheritance)

~ In Canada, settler colonialism, racism, and other forms of oppression are the norm.

~ The COVID-19 pandemic has lead to a surge in anti-Asian racism, but the sentiment has existed for centuries.

~ Race and racism has been upheld by white supremacy to create a hierarchy of humanity to justify colonialism and slavery.

-

- Our families and other people/institutions in our environment teach us about ourselves and the world

~ Can include following or resisting the Canadian status quo of oppression

~ Can include mainstream Canadian culture and our ancestral cultures

-

- Internalization of these beliefs

~ As children, it is natural for us to trust and believe in what the adults in our lives our tell us.

~ Some beliefs may be helpful, and some others may not be.

~ Our beliefs can impact our well-being or self-esteem.

-

- Choosing our legacy

- Recreate the norm (go back to #1) OR

- Choose a different path

- Choosing our legacy

WELLNESS FLOWER

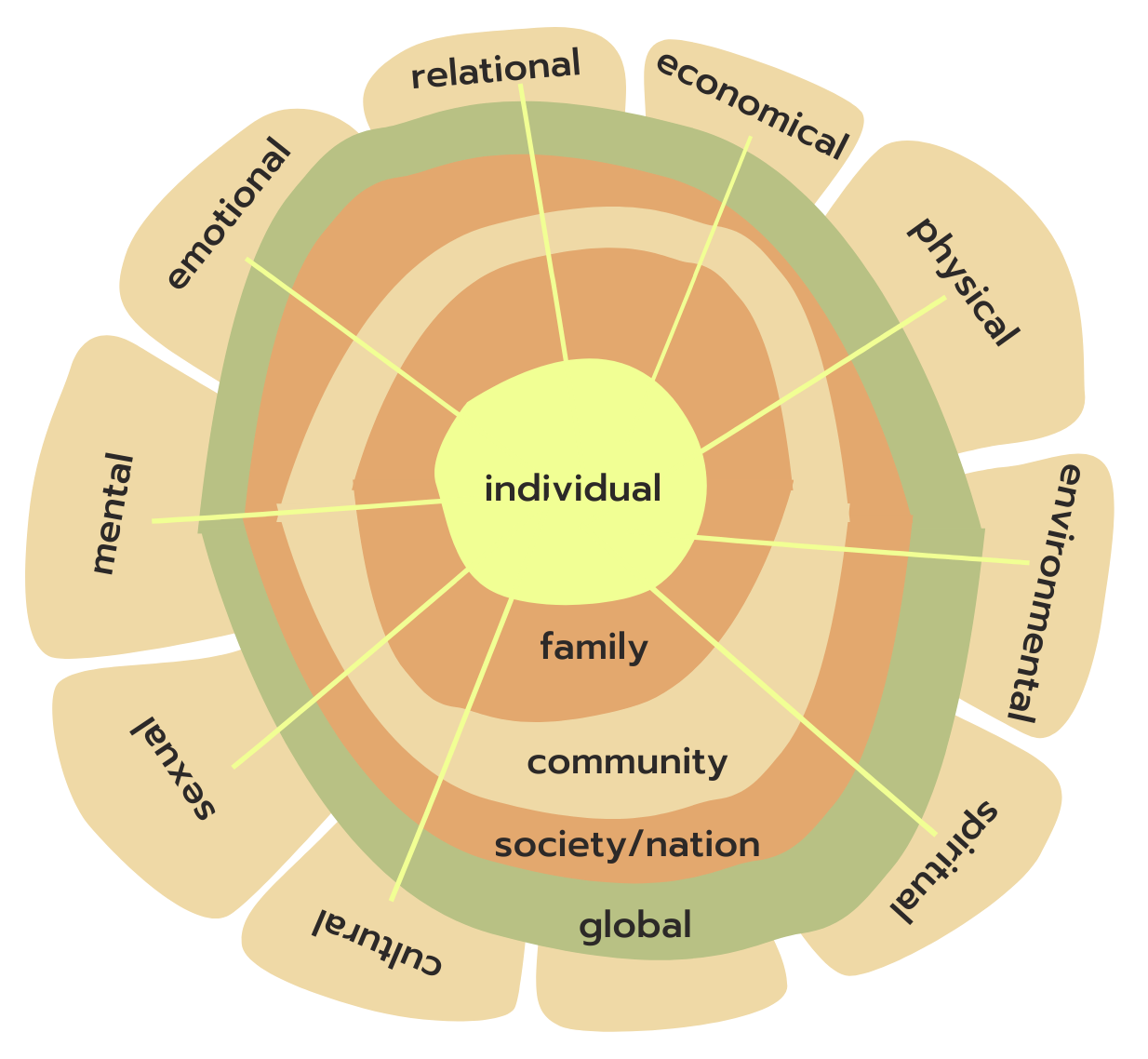

This flower represents how health and wellness is holistic and interconnected within larger systems of people. Therefore mental health does not exist in isolation and must be considered along with physical, emotional, relational, spiritual, cultural, etc. well-being within intergenerational families, communities, societies, and the world.

Image description: The wellness flower contains layers in the centre, going from individual to family, community, society/nation, and global. Rays emanate from the middle out to the petals. Each petal has a different word in it: cultural, sexual, mental, emotional, relational, economical, physical, environmental, and spiritual.

Individual: What is your perspective of wellness? Which aspects are most important to you? How do they interconnect?

Family/Intergenerational: What role does family play in your overall wellness?

Community: Which communities are you a part of (e.g, sports teams, school clubs, friend groups, etc.), and how do they relate to your wellness?

Society/Nation: How would you describe the society in which you live, and what impact does it have on your wellness?

Global: How are these aspects of wellness affected on a global scale? Why is this important to understand?

Wellness is more than the absence of illness, and can actually co-exist with illness. You deserve to flourish and thrive.

INTERGENERATIONAL INFLUENCES

Although wellness includes all of these interconnected aspects, we wanted to especial y highlight the significance of the intergenerational dimension. We are the culmination of the generations before us and they shape our current understandings and realities. Some examples of how intergenerational factors can impact our present day well-being include:

~ Intergenerational conflict: most people experience conflict with their parents and grandparents, but sometimes that conflict is due to cultural differences which can add complexity to the situation, such as if your parent was born in a different country but you grew up in Canada, signal ing different levels of acculturation (identification with the mainstream);

~ Intergenerational trauma: if your family faced traumatic circumstances before, during, or after migration to Canada, the effects of trauma could be passed down generations socially and/or genetically;

~ Intergenerational resilience: just like trauma, strength and resilience can be transmitted between generations, such as through ceremony, art, stories, dance, and language.

Sometimes intergenerational challenges and gifts are not talked about within our families for a number of reasons, but that does not diminish their influence or the inner wisdom you hold about them. You can use this space to reflect on these intergenerational influences (values, strengths, lessons, challenges, etc.) on your wellness:

Cultural considerations for intergenerational conflict

As an Asian person, do you sometimes wonder why you are expected to listen to and obey your parents and grandparents more than others?

The answer might lie in filial piety, which is the cultural value of respecting, supporting, and taking care of your parents and elders.

Through filial piety, not only must you be good to your parents, but you are also expected to maintain a good name for the family through achievements and conduct outside the home. This is also known as saving face. While filial piety can feel like a burden or result in shame, it can also strengthen family connections.

Another source of intergenerational conflict could be a difference in expectations for identity exploration, particularly around gender, sexuality, and dating.

For example, if your family upholds ideas of racial/ethnic purity, they may only approve if you date within your racial/ethnic group. On the other hand, for some parents, dating at al is considered forbidden until a certain age.

In another example, depending on your family’s beliefs, they may hold negative views of queer and/or trans people, which may conflict with your values and understandings.

Sometimes, it can feel easier to hide who you are; sometimes, it’s important for survival.

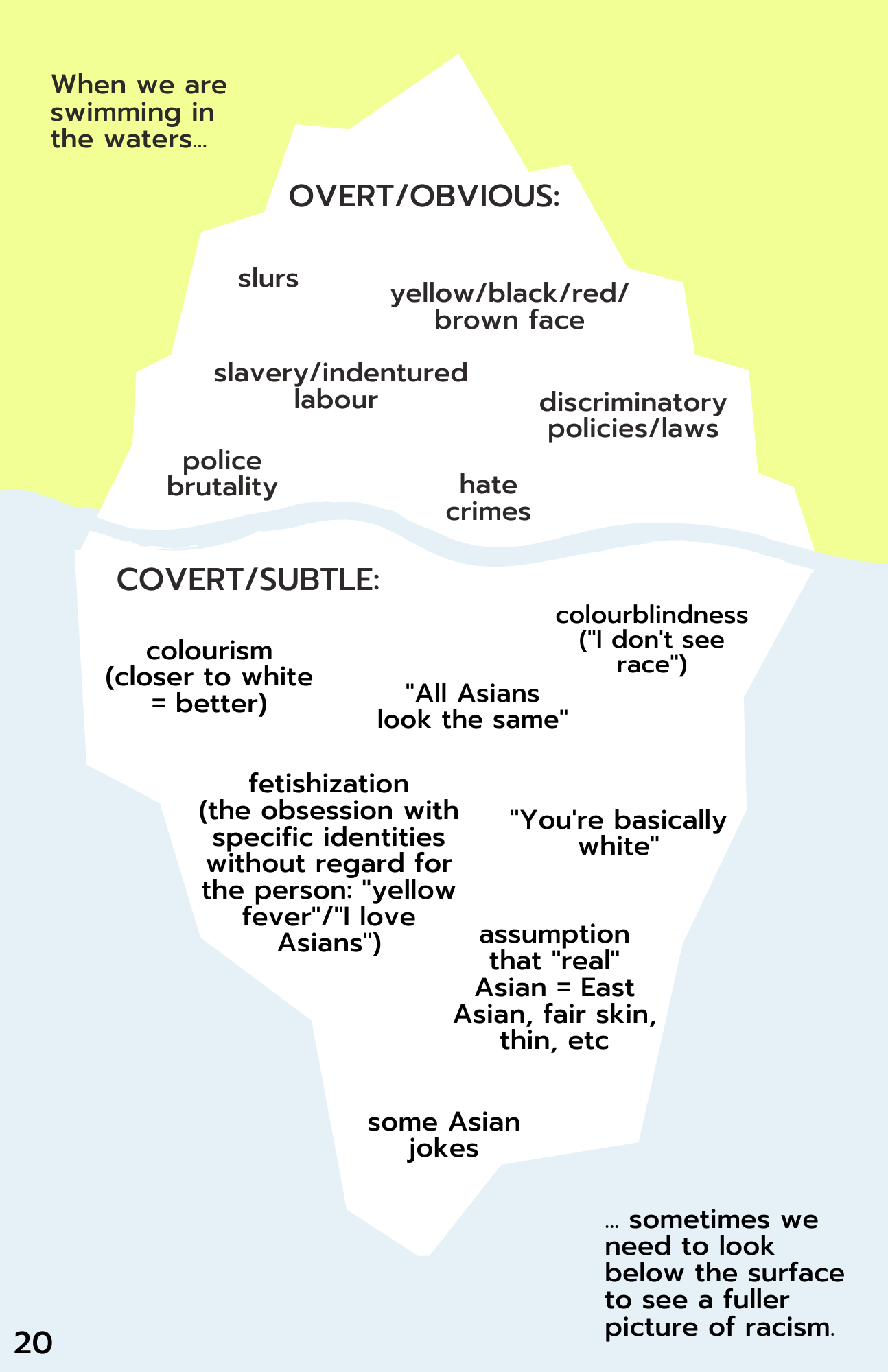

MICROAGGRESSIONS

You might have heard of the term microaggression before, but if not, they are everyday acts of discrimination and bias. They can be intentional or unintentional, but they can cause harm, especially if someone receives a lot of microaggressions.

The ‘micro’ part is about the interpersonal nature of them, as opposed to macroaggressions which exist on societal and institutional levels, and is not meant to minimize their impact.

Three kinds of microaggressions:

- Microassault: conscious, deliberate oppressive behaviour, often highlighting and promoting exclusion (e.g., “Go back to where you came from”)

- Microinsults: unintentional, subtle discriminatory snubs that target difference (e.g., “Your English is so good”)

- Microinvalidation: covertly undermines someone’s experience often with a “colourblind” attitude (e.g., “Asians don’t experience racism anymore”)

Check out the video, ‘How microaggressions are like mosquito bites,’ for more (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hDd3bzA7450)

Sometimes microaggressions can look like compliments or general curiosity, but they can be distinguished because they diminish the humanity of the person they are aimed at.

For example, “All Asians are good at cooking,” reduces people to a stereotype, and only asking racialized people, “Where are you from?” conveys that they do not belong.

Microaggressions are important to understand because they function to continue marginalizing people, whether that is what the perpetrator meant to or not. They remind us that we are not good enough or we are too different to fully belong.

When we regularly experience racial microaggressions, the stress of them can lead to something called racial battle fatigue, which can also negatively impact our well-being. Microaggressions also maintain and further entrench the systems of oppression we live in, continuing the cycle of internalization.

Can you remember a time when you experienced a microaggression? How did it impact you?

Image description: Side view of an iceberg in water. The top portion describes overt/obvious forms of racism, including slurs, yellow/black/red/brown face, slavery/indentured labour, police brutality, hate crimes, and discriminatory policies/laws. The bottom section has examples of covert/subtle forms of racism, including colourism (closer to white = better), “All Asians look the same,” colourblindness (“I don’t see race”), fetishization (the obsession with specific identities without regard for the person: “yellow fever”/”I love Asians”), assumption that “real” Asian – East Asian, fair skin, thin, etc., and some Asian jokes. Outside of the iceberg are the words: When we are swimming in the waters … sometimes we need to look below the surface to see a fuller picture of racism.

BRAIN BREAK 🙂

“On grey days, flowers still bloom.

The news reports the sakura trees in Japan are blooming months early this year. On account of the typhoons and the extreme weather and all that. The cherry blossoms don’t know any better.

I think they’re just trying to survive.”

– Erica Hiroko, excerpt from For the Dreamers https://briarpatchmagazine.com/articles/view/for-the-dreamers 21

BUSTIN’ MYTHS

Model Minority: The belief Asians excel in school/life and have no problems, but it doesn’t allow space for real life struggles and is used to harm other racialized/nonwhite people, especially Black people.

Perpetual foreigner/yellow peril: The notion that East Asians don’t belong and are always outsiders. This disregards history (sometimes spanning centuries) and is complicated by participation in colonialism on unceded territory.

Good immigrant/bad immigrant dichotomy: The pressure to conform to Canadian culture, ideals, behaviour, beliefs, and so on to be seen as a “good immigrant” or else be labelled as a “bad immigrant.” This dichotomy means integration as really just assimilation.

Multiculturalism: Canada asserts values of diversity & equality, but in reality, discrimination, bias, prejudice, oppression, racism, and ethnocentrism are still pervasive and multiculturalism can be used to mask it.

Meritocracy: A system whereby whomever is the best or most qualified is successful, but it ignores systemic barriers, like poverty and racism, and the value of lived experience.

Doctrine of discovery/terra nullius: The story of how European settlers “found” “Canada”, which is used to assert Canada’s legal right to occupy unsurrendered territories. It went from a belief in how the land was empty of people to the belief land was empty of civilization. In truth, Indigenous peoples and sovereign nations have existed here for thousands of years.

Orientalism: Western depiction of “The East,” which upholds exoticization of Asians and Asia as mysterious, uncivilized, foreign, and inferior. Coined by Edward Said to describe images of Arab culture and people.

Respectability politics: The idea that people, especially people of colour, must act and look a certain way to be recognized or considered valid. It can be used to discredit or even harm people.

Professionalism: The equation of proper behaviour, dress, and hairstyle with a white standard.

CHOOSING YOUR PATH

As you get older, you will gain more power and responsibility to determine your own legacy. What path will you take?

Hey! It’s Qwisun. Remember me? Let’s say I decide to choose Option #1: Maintaining the dominant status quo, or the powerful path of least resistance.

I’m likely conforming to the mainstream norm for survival, or possibly for the benefits. But I also need to understand that I may lose a part of who I am in the process.

Remember that you can redirect yourself at any time!

Maybe this looks like…

- Going along with or making jokes that degrade my race or ethnicity…

- Distancing myself from people of the same ethnicity…

- Wishing I was white/had lighter skin…

- Overemphasizing my Canadian-ness to prove I belong here…

These are examples of internalized racism, a common risk of following the norm.

By recreating the status quo, I am (possibly unconsciously or unintentionally) engaging in harm against other marginalized peoples. Not only am I maintaining systems that oppress me, but I am also upholding and contributing to the oppression of racialized, trans, poor, disabled, and otherwise marginalized peoples.

And say I (Macayla) choose another option, a more difficult and sometimes uncomfortable journey.

This can mean choosing which lessons you have received from your family and Canadian society to honour and keep or change.

This also means choosing to take care of myself, grow self-awareness, and listen to what my body is telling me it needs!

Because our society expects constant productivity and facing racism every day can be exhausting, choosing rest and self-care are important acts of resistance and self-preservation.

Fostering wellness is less about self-regulation to be ‘normal’ and more about healing ourselves and building resilience so that we can better care for each other and stand in solidarity as strong families and communities.

You don’t have to do this alone! Who are some supportive people you can reach out to?

This path is also about choosing to recognize your own humanity, which includes:

-

-

- refusing to believe your culture is inferior or less valuable and connecting to your ancestral culture(s).

- understanding you will make mistakes and taking responsibility for them.

-

RELATIONSHIPS OF SOLIDARITY

-

-

- Performative allyship is the appearance of allyship with marginalized groups (e.g., hashtags), but lacks concrete actions or change, versus

- Solidarity, on the other hand, is working in more meaningful ways to support others and reduce harm. It can be more challenging as it requires genuine action and new ways of being in the world.

-

Divesting from white supremacy/settler colonialism and unlearning settler mentality. Ask yourself: How am I invested in maintaining the status quo? How do I feel entitled to be here? How can I change that? How can I keep uncovering and challenging myths settler colonialism/Canada taught me?

Recognizing your privileges, understanding how they impact your perspective of the world and influence on others, and using them to advocate for justice without speaking over others.

-

-

- Listening and learning, growing empathy, focusing on the message instead of how it’s said

- Continuing the conversation with the people around you (e.g., families, peers, teachers, siblings, cousins, internet friends, others)

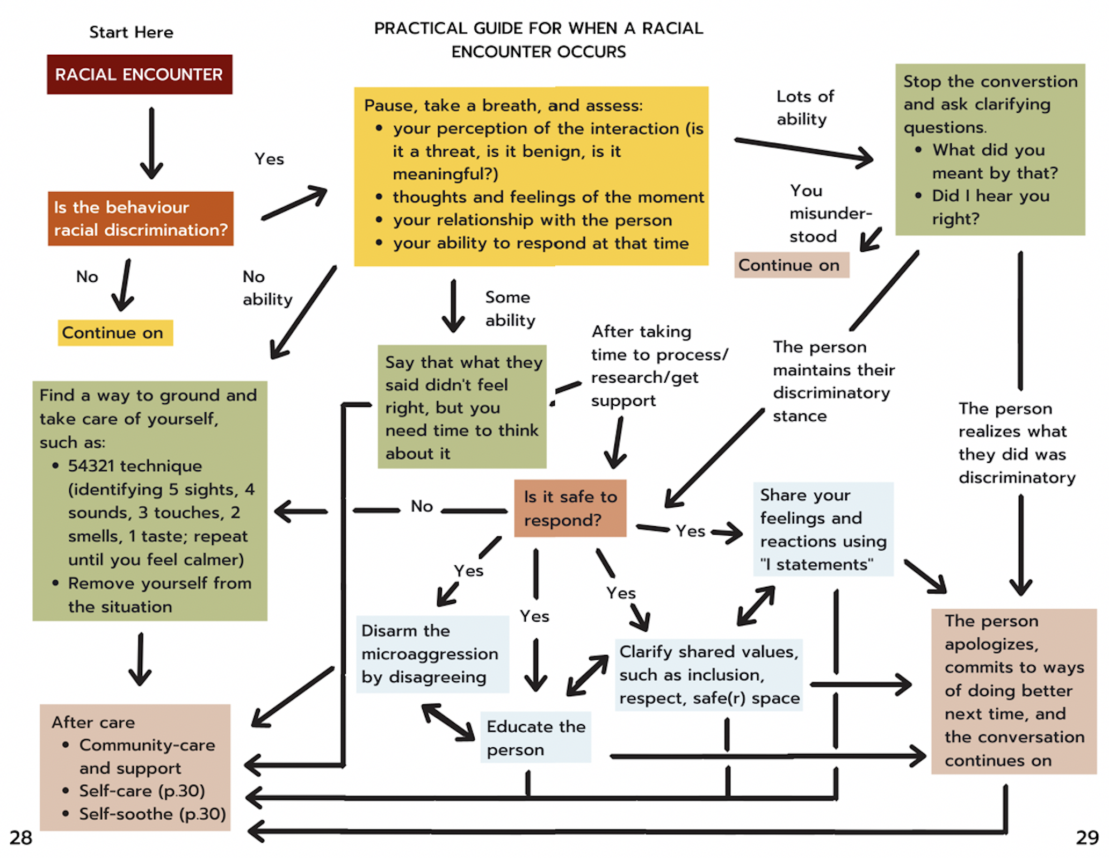

- Speaking up against discrimination and bias (see flow chart on next page)

- Building relationships founded on justice, accountability, and love

- Volunteering/getting involved with a cause you believe in

-

PRACTICAL GUIDE FOR WHEN A RACIAL ENCOUNTER OCCURS

Image description: flow chart of potential ways to respond when a racial encounter occurs. It starts with the racial encounter and asks if the behaviour was racial discrimination. If the answer is no, the conversation can continue, but if the answer is yes, the guide suggests pausing, taking a breath, and assessing: your perception of the event (is it a threat, benign, or meaningful?); thoughts and feelings of the moment; your relationship with the person; and your ability to respond at the time. If the answer is no ability, you can find a way to ground and take care of yourself, such as: the 54321 technique (identifying 5 sights, 4 sounds, 3 touches, 2 smells, 1 taste; repeat until you feel calmer), and/or remove yourself from the situation. If you have some ability to respond, the guide offers saying that what they said didn’t feel right, but you need more time to think about it. You can then later process the interaction, do research, and/or get support. If you have lots of ability, the guide indicates stopping the conversation and asking clarifying questions: 1) What did you mean by that? or 2) Did I hear that right? If you find out you misunderstood what they were saying, you can continue the conversation. Sometimes, through the clarifying questions, the person realizes what they said was discriminatory, so they apologize, commits to doing better next time, and the conversation continues on. In cases where the person maintains their discriminatory stance, the guide questions if it is safe to respond. If not, then it points to ways to ground and care for yourself mentioned already. If it is, the guide provides four options which can be used alone, together, and/or in various orders: disarm the microaggression by disagreeing; education the person; clarify shared values, such as inclusion, respect, safe(r) space; and share your feelings and reactions using “I statements.” The other person may then realize what they did was discriminatory, apologize, commit to doing better, and the conversation continues. All of the various pathways in this guide end in aftercare, including community care, self-care, and self-soothing.

SELF-SOOTHING/SELF-CARE

Self-Soothing: Self-soothing is a short-term way to take care of and treat yourself. While self-soothing techniques may help in the moment (e.g., eating junk food), they can be harmful if taken to the extreme (e.g., excessive eating, over-drinking or over-binge-watching).

Self-care: Self-care is a long-term investment for your wellness. Sometimes self-care strategies may not feel good in the moment, but they are a way of taking care of your future self (e.g., cooking food, going to bed early.) Be careful of ignoring relational obligations and responsibilities.

What are some self-care strategies that might work for you?

Self-care/Self-soothing Tool Kit

First, how will you know you will need to engage with self-soothing/self-care techniques? What are some physical, mental, emotional, relational, etc. signs?

Tired? Grumpy? Sad? Troubles concentrating?

Sometimes we are not able to plan a self-care session so we often self-soothe. As such, it can be helpful to prepare some tools in advance so they are ready when you are feeling overwhelmed in the moment. What are some self-soothing tools for your tool kit? E.g., grounding or fidget object that helps you stay calm.

One technique to help reduce stress is called box breathing. It is used by athletes and nurses to help stay calm. You can imagine drawing a box while doing it.

1) Sit upright in a comfortable position with feet flat on the ground.

2) Slowly exhale from your mouth, releasing all the air from your lungs.

3) Gently inhale through your nose, slowly counting to 4.

4) Hold your breathe for another slow count to 4.

5) Calmly exhale out of your mouth again, slowly counting to 4.

6) Hold your breathe again for 4 slow seconds.

7) Repeat steps 3-6 as needed.

ACCOUNTABILITY

Sometimes we may be the one who says a microaggression to someone else. In those cases, we must be careful not to go into defensive mode when someone points it out.

Instead, try to slow yourself down, really take in what they are telling you, apologize, make amends, and commit to changing your behaviour. (This does not need to be all at once.)

It can feel embarrassing when someone calls us on a microaggression, but try to remember that they want to stay connected to you and are allowing you the opportunity to be accountable for harm you caused. In other words, they are doing this out of care and giving you a gift of growth.

How can you be accountable to harm you cause?

WHAT’S NEXT?

What’s next requires envisioning a new world and different ways of being in relationship and community with one another.

Use this space to dream up what could be possible. Attach as many pages as necessary.

This is not a passive process. So, what are you committing to doing in the next week? Next year? For the rest of your life? Who can you do this with?

Use this space to brainstorm 🙂

ADDITIONAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We want to acknowledge the project team that guided the development of this zine:

Dr. Fred Chou, R.Psych.

-

- Fred (周敏浩) is an assistant professor in counselling psychology in the department of Educational Psychology and Leadership Studies at the University of Victoria. He identifies as a 2nd generation Chinese Canadian with ancestral roots in the Canton province. He recently became a proud new father and is learning the art of diaper changing.

Prof. Jin-Sun Yoon

-

- Jin-Sun (윤진선) was “made in Korea” but came to Turtle Island (aka Canada) as a child. She is grateful and indebted to Indigenous knowledge keepers and land defenders for sharing so generously a better way to live on this planet as human relatives. She is a Teaching Professor in the School of Child and Youth Care at the University of Victoria who incorporates activism with education.

Dr. Catherine Costigan, R.Psych.

-

- Cathy is a professor in clinical psychology at the University of Victoria. She was raised in the United States by parents with Irish, Swedish, Norwegian, and French backgrounds and immigrated to Canada as an adult. She is also grateful to learn more every day how to bring a social justice and equity lens to her work.

Dr. Nancy Clark

-

- Nancy is of mixed heritage Palestinian and Serbo Croation, first generation Canadian. Nancy is an assistant professor at the University of Victoria’s School of Nursing and studies intersectionality, and the mental health of population groups affected by displacement.

We want to acknowledge that this work draws from the collective wisdom of knowledge keepers, advocates, scholars, and the community. To see the references that this zine has incorporated ideas from, see www.growthandsolidarity.ca. We also recognize that language and knowledge is in constant flux so information in this zine may not be the most up-to-date.

The project was funded by the University of Victoria Faculty of Education

For more information and for resources, please visit: www.growthandsolidarity.ca

Or email us at: hello@growthandsolidarity.ca